By ANISH KOKA

The most recent fiction dressed up as science about COVID comes to us courtesy of a viral Washington Post article. “How the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally may have spread coronavirus across the Upper Midwest” screams the headline. The charge made is that “within weeks” of the gathering that drew nearly half a million visitors the Dakota’s and adjacent states are experiencing a surge of COVID cases.

The Sturgis Rally happens to be a popular motorcycle rally held in Sturgis, South Dakota every August that created much consternation this year because it wasn’t cancelled even as the country was in the throes of a pandemic. While some of the week long event is held outdoors, attendees filled bars and tattoo parlors,(and that too without masks!), much to the shock and chagrin of the virtuous members of society successfully able to navigate life via zoom, amazon prime, and ubereats.

This particular Washington Post article’s sole source of data comes from a non-profit tech organization called The Center For New Data that attempted to use cellphone data to attempt to track spread of the virus from the Sturgis rally. Unfortunately, tracking viral spread using cellphone mobility data is about as hard as it seems. The post article references only 11,000 people that were able to be tracked out of a total of almost 500,000 visitors, and isn’t able to assess mask wearing, or attempts at social distancing. How many bars are there to stuff into in Sturgis anyway?? And so it isn’t surprising that even in an article designed to please a certain politic, this particular sentence appears:

“But precisely how that outbreak unfolded remains shrouded in uncertainty.”

The other striking feature of the article is the timing of this ptome to journalistic excellence. The article is published in the latter half of October precisely because South Dakota is documenting its highest numbers of new cases now. It doesn’t seem to matter that the Sturgis Rally was held in early August, more than 2 months prior to the recent spike in cases. The Post article spends the majority of its time meandering through a few anecdotes from rally attendees who have finally seen the error in their ways, but provide no other data points to substantiate the condescension of the blue-checkmark twitterati that were all too happy to amplify the article.

In fairness, this isn’t the first time a scarlet C has been attempted to be hung on Republican Governor of South Dakota, and the band of deplorables she leads. The unabashed Trump supporting Governor has had the conventional public health experts on mute for much of the pandemic. The South Dakotan approach has emphasized private personal responsibility and was one of only eight states to eschew stay-at-home, or safer-at-home orders. The really annoying aspect of this approach to public health autocrats was that it seemed to work really well, as new COVID cases leading up to the Sturgis rally numbered in the 5o’s and 60’s per day while other, admittedly larger states, had outbreaks in the tens of thousands per day.

The current attempts to tie increasing cases to a gathering that took place months earlier is squarely in the realm of politics, not science. After almost eight long months the citizens of the globe are weary, and are restarting life out of necessity. Schools are opening, traffic into cities is building, and grandparents are hugging their grandkids again. Tracking spread of the virus as this happens is simply a reflection of the social interactions that have come to define life. Testing for COVID is ubiquitous enough at this point to have largely become a meaningless exercise used primarily to support shoddy scholarship that generates a clickbait headline. If it was politically expedient to connect France’s recent spike in COVID case to the Sturgis Rally, some ‘researcher’ would find a way to make science say it was so.

An earlier, more scholarly attempt to make the Sturgis Rally the nation’s largest super-spreading event provides a particularly good example of how science bends to politics. In September, economists tried to use another cellphone dataset to show that counties across the nation that contributed more travelers to the Sturgis Rally saw a much higher rise in COVID cases than those that sent relatively few travelers. A closer read of the paper finds the wheels start coming off this particularly poorly constructed narrative almost immediately. One would think that researchers intent on demonstrating a COVID apocalypse triggered by a mass gathering would use deaths, but instead COVID cases are used. The authors explain that their reason for using cases is because of the relatively low level of mortality since the Sturgis event. At the time the article was published September 2nd, there had been one recorded death since the rally.

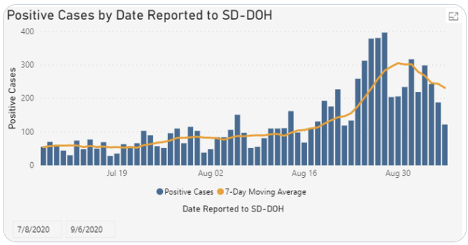

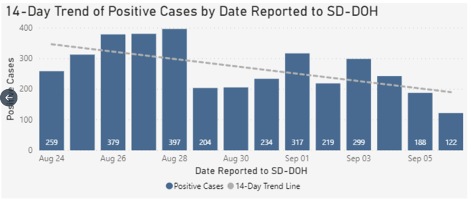

It is true that South Dakotans appear to obey the natural laws of viral spread. As people gather and socialize doing the things they value, whether that be at motorcycle rallies or the local Target, cases rise. Two weeks after the Sturgis rally, South Dakota goes from seeing fewer than a 100 new cases per day to almost 400 new cases per day.

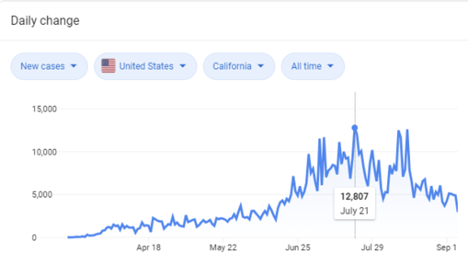

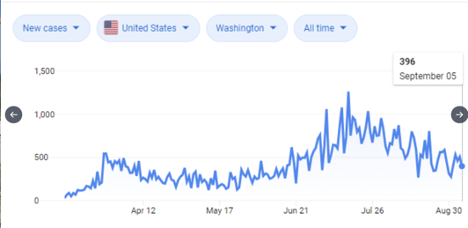

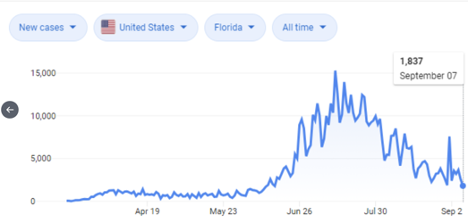

To put these numbers into context, one need only look at the rise in cases in California, Washington and Florida, all seemingly quiet until a few weeks after massive gatherings in major cities during the Memorial Day Weekend.

Fascinatingly the same researchers confident about the link between national superspreading and the Sturgis Rally also found no link between widespread Memorial day protests and a spike in cases 2 weeks later.

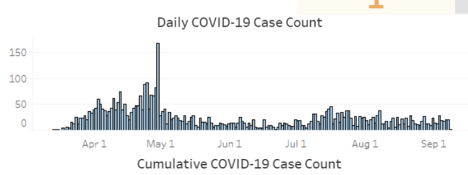

The data in early September, almost one month after the Sturgis Rally actually suggests S. Dakotans had a reasonably small uptick in cases that was already beginning to dissipate according to the snapshot available from the South Dakota COVID dashboard.

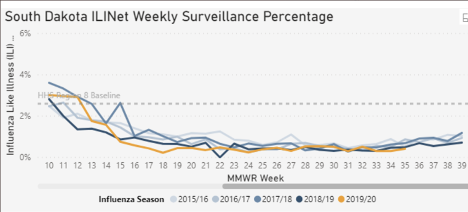

And its not just PCR positivity, even the weekly influenza like illness reporting trends year-over-year, shows no significant spike compared to prior years.

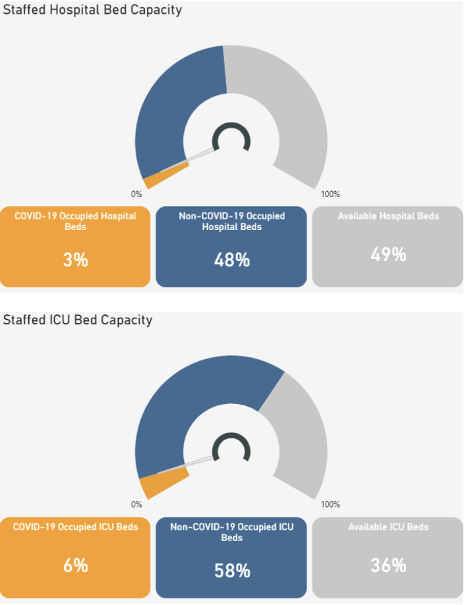

The danger of superspreader events is that they create a conflagration that overwhelms hospitals, yet the hospital occupancy data In South Dakota shows almost 50% of regular hospital beds, and 36% of ICU beds were empty one month after the Sturgis Rally.

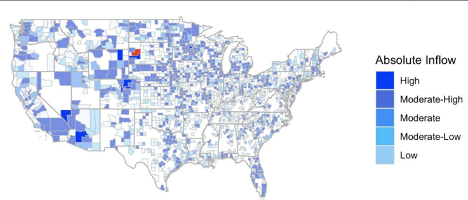

The real meat in this scholarly work, of course, is the proposition that Sturgis spread the virus far and wide. The paper sought to demonstrate this by by showing counties across the country that contributed a high number of attendees to the Sturgis Rally saw higher rates of COVID spread in the weeks that followed.

The following national map shows the counties that were noted to contribute a high number of travelers to the sturgis rally. The deepest blue are high inflow counties, that were found to have an increase in cases between 6-12% after the Sturgis Rally. Conversely, low inflow counties appeared to have no increase in new COVID cases.

This would appear to be concerning, visual evidence of COVID spread directly as a result of the Sturgis rally, until one actually uses the nice map to take a look at outbreaks in high inflow counties. Here is one of the graphs of COVID cases in the deep blue high inflow Weld County, Colorado. Even an electron microscope wouldn’t be able to manufacture a meaningful spike three weeks after the Sturgis even in early August..

Weld County, Colorado

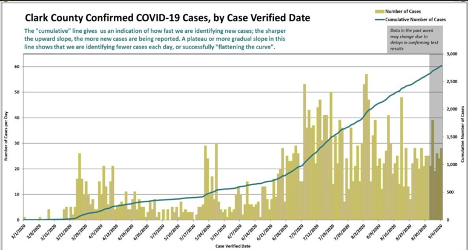

The next high inflow county of interest is the home of Las Vegas, which also shows absolutely no visual evidence of chaos unleashed after the August gathering. The spike in cases here instead seems to time out well with casino openings in mid June.

Clark County, Nevada

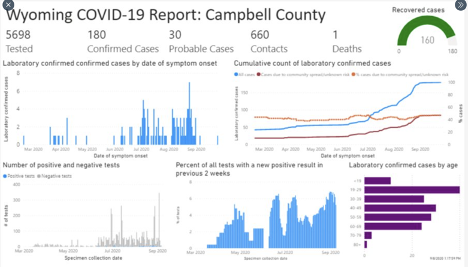

Campbell County, Wyoming, another high inflow county, is perhaps more promising for the Sturgis superspreader narrative on first glance. There appears to be a spike in cases about 2 weeks after Sturgis, but a closer look at the y-axis shows the spike in cases was 8 new cases in one day. Not 80, not 8000, but eight cases.

Campbell County, Wyoming

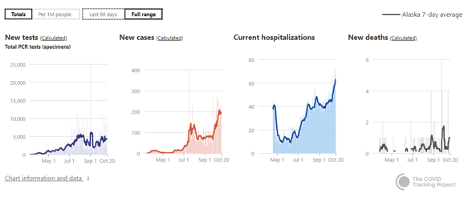

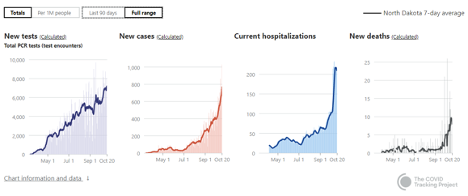

But as cases rise across the nation in October in multiple disparate states, somehow the edifying narrative the Washington Post and other social media influencers are latching onto is that the Sturgis rally was the unique event that set fire to the midwest. Never mind that non-contiguous Alaska and Sturgis-adjacent North Dakota have new case/hospitalization peaks that appear to mirror each other by both accelerating in October, well after one would expect Sturgis to be responsible.

Alaska

North Dakota

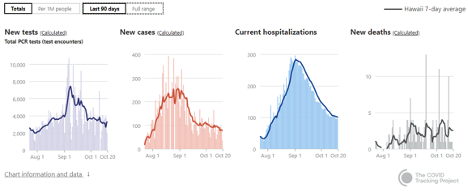

On the other hand, Hawaii appears to have some cause to blame its epidemic on the irresponsible Dakotans from Sturgis based on the timing of its new case and hospitalization peaks. It’s just too bad motorcycle traffic between Hawaii and South Dakota is of the non-existent variety.

Even casual observers at this point should realize that Science is in the process of being shaped by politics. Perhaps this has always been so, and it just took COVID to make the contortions transparent. Nonetheless, we live in a world where the answers are known before the research begins and the headlines are written before journalists put pen to paper. This goes well beyond the garden variety cherry picking of research that is the hallmark of all debates, whether they be scientific or political. This is utilizing the research enterprise to manufacture science that suits a particular politic. And so we get a particular focus on Sturgis two whole months after the event because the point is to shame deplorables in states with Republican leadership 3 weeks before a Presidential election. In this brave new world, the science tells us that massive Memorial Day protests don’t trigger viral outbreaks, but motorcycle rallies in South Dakota do. “Science” careens towards science fiction.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist in Philadelphia. He is co-host of the Accad & Koka report. Follow him on twitter @anish_koka.

Spread the love