As the coronavirus surged across the Sunbelt, President Trump told a crowd gathered at the White House on July 4 that 99 percent of virus cases are “totally harmless.”

The next morning on CNN, the host Dana Bash asked Dr. Stephen Hahn, the commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration and one of the nation’s most powerful health officials: “Is the president wrong?”

Dr. Hahn, an oncologist and former hospital executive, certainly understood the deadly toll of the virus, and the danger posed by the president’s false statements. But he ducked the journalist’s question.

“I’m not going to get into who’s right and who’s wrong,” he said.

The exchange illustrates the predicament that Dr. Hahn and other doctors face working for a president who often disregards scientific evidence. But as head of the agency that will decide what treatments are approved for Covid-19 and whether a new vaccine is safe enough to be given to millions of Americans, Dr. Hahn may be pressured like no one else.

Unlike Dr. Anthony S. Fauci or Dr. Francis S. Collins, leaders at the National Institutes of Health who have decades of experience operating under Republican and Democratic administrations, Dr. Hahn was a Washington outsider.

Now seven months into his tenure, with the virus surging in parts of the country and schools debating whether to reopen, the push for a vaccine is intensifying. The government has committed more than $ 9 billion to vaccine makers to speed development, and last week Mr. Trump speculated that one could be ready by Election Day — a timeline that is unrealistic, according to scientists, and shows the strain Dr. Hahn may be under.

Many medical experts — including members of his own staff — worry about whether Dr. Hahn, despite his good intentions, has the fortitude and political savvy to protect the scientific integrity of the F.D.A. from the president. Critics point to a series of worrisome responses to the coronavirus epidemic under Dr. Hahn’s leadership, most notably the emergency authorization the agency gave to the president’s favorite drug, hydroxychloroquine, a decision it reversed three months later because the treatment did not work and harmed some people.

“When you’ve got a White House that is not interested in science, it’s important to have a strong counterweight,” said Dr. Peter Lurie, a former associate commissioner at the F.D.A. who now runs the Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Dr. Hahn, he said, “is not a powerful presence.”

In an interview, Dr. Hahn, 60, defended his record as F.D.A. chief. All of his decisions have been guided by the data, he said, and sometimes, rapidly evolving science has led to policy changes.

“I do not feel squeezed,” Dr. Hahn said. “I have been consistent in my message internally about using data and science to make decisions.”

On the line as he spoke was Michael Caputo, a deputy to Dr. Hahn’s boss, Alex M. Azar II, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services. Since working for the consulting firm of the longtime Trump adviser Roger J. Stone Jr. in the 1980s, Mr. Caputo has been a cheerleader and even, once, a driver for the president.

Dr. Hahn is not allowed to speak to the press without Mr. Caputo or another official on the phone — a marked contrast to the practice under the last F.D.A. commissioner, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a powerful force in Washington who came to the job with years of experience at the F.D.A. and political think tanks. He called reporters whenever he felt like it, which was often.

Dr. Hahn said he didn’t mind the restriction on his press calls.

“I’m going to tell you how I feel and the truth as I know it, regardless of who is listening on the line,” Dr. Hahn said.

But people close to the commissioner point out that if he is too honest, he could be out of a job.

“The president has shown if you disagree with him too much, he fires you,” said Dr. Hahn’s longtime friend and former colleague Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

In late July, Mr. Mahoney noted, the president retweeted a viral video of fringe doctors praising hydroxychloroquine that social media platforms later removed for its misleading claims. One of those doctors had given sermons warning that women having sex with demonic spirits in their dreams can cause certain gynecological ailments.

“To say that any public health official can control what is going on right now is expecting too much for that person,” Mr. Mahoney said.

A ‘catastrophic delay’ in testing

The job of F.D.A. commissioner is a lightning rod in the best of circumstances. Every White House and every Congress has its agendas, from Ronald Reagan’s broad mission to deregulate, to the Obama administration’s specific order not to ban flavored e-cigarettes.

But the F.D.A. has never been pushed as hard as it is being pushed now, when it must vet every new treatment and vaccine for a disease that has already killed more than 160,000 Americans, under a president who downplays the severity of the pandemic and recommends unproven treatments.

“Given when he started, this level of intrusion is all that Steve Hahn has really known, but it is not normal,” said Dr. Margaret Hamburg, who was F.D.A. commissioner for six years under President Barack Obama. “There’s no doubt that the president believes he can massage F.D.A. decisions.”

Before joining the Trump administration, Dr. Hahn had climbed the ranks of academic medicine, spending 18 years at the University of Pennsylvania followed by five years at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, where his last role was chief medical executive. A wine aficionado who studies Italian (his rescue dog is named Baci), Dr. Hahn is known for being affable, perhaps to a fault.

It did not take long for Dr. Hahn to discover the intense scrutiny that came along with his new job.

In late January, when only a handful of coronavirus cases had been recorded in the United States, Dr. Hahn planned to reach out to the chief executives of private companies about developing diagnostic tests, according to four current and former senior administration officials who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the press. Dr. Gottlieb had made the suggestion to Dr. Hahn.

According to two of the officials, Dr. Hahn told them that he had been informed that the Health and Human Services department did not want him reaching out to the companies. Dr. Hahn declined to comment on any communication regarding the companies, but one of the officials said Dr. Hahn expressed disappointment over the situation.

In a statement, Mr. Azar denied giving any such order. “There is not a shred of truth to this. In fact, I encouraged F.D.A. to reach out to industry from the earliest days of the response,” he said. Asked whether someone else in the agency might have conveyed the message, Caitlin Oakley, a spokeswoman for Health and Human Services, said: “H.H.S. has 80,000 employees and I can’t speak for all of them.”

The F.D.A. soon discovered serious problems with the country’s first coronavirus tests issued by its sister agency, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The F.D.A. discovered that there was contamination in two C.D.C. labs, leading to significant delays.

But it took about three more weeks after the F.D.A. confirmed these problems before it allowed state and commercial labs to more easily use their own validated tests. State labs had been stuck with the C.D.C.’s flawed version — losing critical time when hospitals across the country were desperate to isolate infected people.

“This was a catastrophic delay that was a major part of why we had to shut down,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute.

In an effort to respond to public demand for more coronavirus tests, the agency then changed course, permitting scores of companies to sell tests that detect coronavirus antibodies, which show whether someone has been exposed to the virus in the past.

Many of the tests failed and few companies bothered to alert the F.D.A., as required. The agency has taken some off the market, but many shoddy tests are still being sold.

Unproven treatments

While his administration’s testing missteps were fueling the early pandemic, Mr. Trump began a crusade for what were then chiefly known as malaria and lupus drugs, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine.

The Coronavirus Outbreak ›

Frequently Asked Questions

Updated August 6, 2020

Why are bars linked to outbreaks?

- Think about a bar. Alcohol is flowing. It can be loud, but it’s definitely intimate, and you often need to lean in close to hear your friend. And strangers have way, way fewer reservations about coming up to people in a bar. That’s sort of the point of a bar. Feeling good and close to strangers. It’s no surprise, then, that bars have been linked to outbreaks in several states. Louisiana health officials have tied at least 100 coronavirus cases to bars in the Tigerland nightlife district in Baton Rouge. Minnesota has traced 328 recent cases to bars across the state. In Idaho, health officials shut down bars in Ada County after reporting clusters of infections among young adults who had visited several bars in downtown Boise. Governors in California, Texas and Arizona, where coronavirus cases are soaring, have ordered hundreds of newly reopened bars to shut down. Less than two weeks after Colorado’s bars reopened at limited capacity, Gov. Jared Polis ordered them to close.

I have antibodies. Am I now immune?

- As of right now, that seems likely, for at least several months. There have been frightening accounts of people suffering what seems to be a second bout of Covid-19. But experts say these patients may have a drawn-out course of infection, with the virus taking a slow toll weeks to months after initial exposure. People infected with the coronavirus typically produce immune molecules called antibodies, which are protective proteins made in response to an infection. These antibodies may last in the body only two to three months, which may seem worrisome, but that’s perfectly normal after an acute infection subsides, said Dr. Michael Mina, an immunologist at Harvard University. It may be possible to get the coronavirus again, but it’s highly unlikely that it would be possible in a short window of time from initial infection or make people sicker the second time.

I’m a small-business owner. Can I get relief?

- The stimulus bills enacted in March offer help for the millions of American small businesses. Those eligible for aid are businesses and nonprofit organizations with fewer than 500 workers, including sole proprietorships, independent contractors and freelancers. Some larger companies in some industries are also eligible. The help being offered, which is being managed by the Small Business Administration, includes the Paycheck Protection Program and the Economic Injury Disaster Loan program. But lots of folks have not yet seen payouts. Even those who have received help are confused: The rules are draconian, and some are stuck sitting on money they don’t know how to use. Many small-business owners are getting less than they expected or not hearing anything at all.

What are my rights if I am worried about going back to work?

- Employers have to provide a safe workplace with policies that protect everyone equally. And if one of your co-workers tests positive for the coronavirus, the C.D.C. has said that employers should tell their employees — without giving you the sick employee’s name — that they may have been exposed to the virus.

What is school going to look like in September?

- It is unlikely that many schools will return to a normal schedule this fall, requiring the grind of online learning, makeshift child care and stunted workdays to continue. California’s two largest public school districts — Los Angeles and San Diego — said on July 13, that instruction will be remote-only in the fall, citing concerns that surging coronavirus infections in their areas pose too dire a risk for students and teachers. Together, the two districts enroll some 825,000 students. They are the largest in the country so far to abandon plans for even a partial physical return to classrooms when they reopen in August. For other districts, the solution won’t be an all-or-nothing approach. Many systems, including the nation’s largest, New York City, are devising hybrid plans that involve spending some days in classrooms and other days online. There’s no national policy on this yet, so check with your municipal school system regularly to see what is happening in your community.

At a March 19 news conference, Mr. Trump said that the drugs would be approved for Covid-19 as well, thanks to the quick work of the F.D.A. and Dr. Hahn, in particular. “I’d shake his hand, but I’m not supposed to do that,” Mr. Trump said. “But he’s been fantastic.”

It was startling news, given that scant data had shown that the drugs could treat the disease. Speaking immediately after the president, Dr. Hahn tried to hedge, saying that clinical trials were needed. But he also acknowledged Mr. Trump’s personal role in the matter, noting, “that’s a drug that the president has directed us to take a closer look at.”

Nine days later, the F.D.A. issued an emergency authorization for the drugs in patients hospitalized with Covid-19.

“The science they had wasn’t sufficient to make that decision,” said Dr. Luciana Borio, who worked as a top F.D.A. scientist during the Ebola and Zika outbreaks and was also director for medical and biodefense preparedness at the National Security Council under the Trump administration. “I don’t know how they say it’s not politics.”

In June, the agency revoked its emergency authorization after it found that more than 100 Covid-19 patients taking the drugs developed serious heart disorders, including 25 who had died.

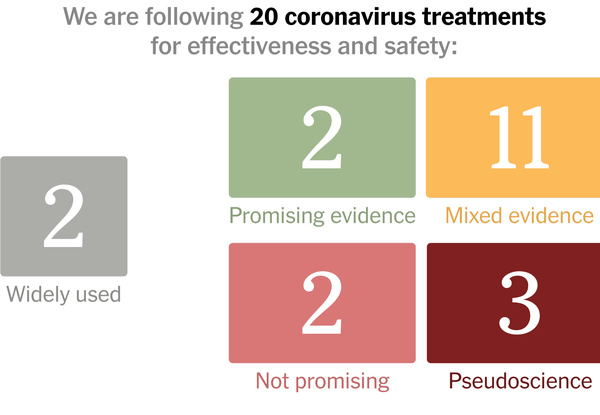

Hydroxychloroquine wasn’t the agency’s only authorization lacking solid evidence, some scientists say. In April, the F.D.A. partnered with the Mayo Clinic to give Covid-19 patients across the country access to convalescent plasma, even though the jury is still out on whether it works. The agency also gave emergency authorization to several blood purification systems that critics say don’t help patients get better.

“F.D.A. is giving approvals right, left and center,” said Dr. Swapnil Hiremath, a nephrologist at the University of Ottawa and a critic of the blood filtration devices. “You need data.”

After a month of playing defense with an exasperated scientific community, Dr. Hahn found himself on CNN, again struggling to cover for Mr. Trump. This time, he was asked about the president’s disturbing suggestion that injecting disinfectant might be a good way to treat Covid-19.

“I think this is something a patient would want to talk to their physician about,” Dr. Hahn replied. Then he seemed to remember his medical training. “And no, I certainly wouldn’t recommend the internal ingestion of a disinfectant.”

Many of Dr. Hahn’s colleagues, as well as longtime observers of the F.D.A., say that Dr. Hahn is doing his best to uphold the mission of his agency under exceedingly difficult circumstances.

“I think some mistakes have been made. I think probably Dr. Hahn has learned from those mistakes,” said Diana DeGette, a Democratic congresswoman from Colorado who heads the oversight panel of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which has jurisdiction over the F.D.A. “My perception is he’s trying to accommodate real efforts to treat the virus.”

The vaccine stakes

More than 30 experimental coronavirus vaccines are now in clinical trials, with several companies racing to have the first product in the U.S. ready by the end of the year. With the public highly skeptical of these new vaccines, the F.D.A.’s vetting process will be Dr. Hahn’s biggest test yet.

In June, the F.D.A. issued guidelines saying that, in order to be approved, a coronavirus vaccine must be at least 50 percent more effective than a placebo, on par with most flu vaccines.

Worried that an ineffective or unsafe vaccine would fan fears about immunizations, a bipartisan trio of senators introduced legislation last week to improve oversight of the vaccine approval process, and nearly 400 health experts sent a letter urging Dr. Hahn to use the agency’s vaccine advisory group. On Friday, the commissioner and two of his deputies wrote in JAMA that “transparent discussion” by the advisory panel would be needed before any vaccine authorization or approval.

The president, for now, appears to be pleased with the commissioner.

Dr. Hahn was “really speeding up the process of therapeutics and vaccines,” Mr. Trump said at a recent news conference on drug pricing. “It’s very important, Stephen. Can you move it faster, please, OK? Thank you, great job.”