Advertisement

Supported by

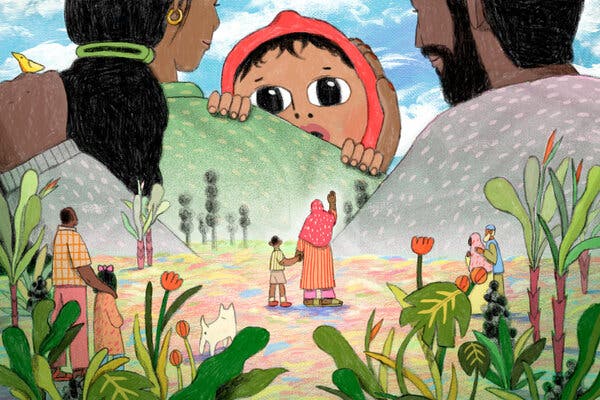

Your Pandemic Baby’s Coming Out Party

Haven’t seen your family in a while? Have a grandchild you’ve never met? Visiting may be awkward at first but you can get through it.

No one in Deena Al Mahbuba’s family has met her daughter, Aara. She was born at the end of 2019, extremely premature. By the time Aara left the hospital for her home outside Boston in mid-June, the world was already months into Covid-19 lockdowns. Ms. Mahbuba’s close relatives, along with her husband’s, all live in Bangladesh. The couple moved from there in 2013.

Family members have done their best to stay connected, but Ms. Mahbuba, a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wishes her relatives were nearby. Her older siblings have kids of their own and could help her soothe Aara when she’s sleepless.

Or they could show her how they introduced foods to their own babies; Aara, now 15 months old, struggles with new foods after having been tube-fed in her early life. Ms. Mahbuba also hopes Aara will learn to speak Bengali, but worries she needs exposure to the language from people besides her parents.

“Sometimes I feel really sad,” Ms. Mahbuba said. “I feel like there is a gap happening, and sometimes I worry this gap is going to be stretched out day by day.”

Even grandparents, aunts or uncles in the same country as babies born during Covid-19 have been kept away by travel restrictions and other precautions. Darby Saxbe, an associate professor at the University of Southern California, said her lab started following 760 expectant parents in the spring of 2020 to study their mental health, social connection and other factors. In open-ended survey responses, many participants reported that they hadn’t been able to see extended family.

The first pandemic babies are becoming toddlers this spring, which means entire infancies have passed while children and their parents were isolated from their loved ones. Even as families mourn the missed cuddles, though, experts say the gap isn’t likely to have any long-term effects. Kids and their relatives can make up for lost time when they reunite. In the meantime, families can take steps to keep those missing relatives present in a child’s mind.

Reaching Across the Gap

Infancy is an important window of time for bonding, said Sarah Schoppe-Sullivan, an Ohio State University child psychology professor, and not just because it’s your only chance to catch those squishy cheeks and sniffable heads. “Infancy is the period during which children are biologically predisposed to form close relationships with important caregivers,” Dr. Schoppe-Sullivan said.

This is an element of attachment theory, an area of psychology research that’s been around for several decades. (Not to be confused with attachment parenting, a philosophy from the 1980s that espouses a whole lot of baby-wearing.) Studies suggest that babies are primed to bond tightly with one or more caregivers. Once a child has a strong attachment to someone, that person becomes a “secure base,” the theory goes. The child looks to that person for reassurance in moments of distress. In calmer times, secure attachments give kids confidence to explore and learn from their environments.

But relatives who miss this window don’t need to worry, Dr. Schoppe-Sullivan said. The theory says that when infants form secure attachments, they’re also forming the capacity for relationships in the future. That means the bonds parents have built with their babies during coronavirus-induced isolation may help those babies connect with relatives who live far away — whenever they finally visit.

And today’s infants and toddlers won’t recall these absences. The older siblings of the pandemic babies may not remember a gap in visits from Nana, either. Because of what’s known as childhood amnesia, most people remember few events that occur before age 3 or so. Even though grandparents may be grieving for the milestones they missed this year, “The child will not remember who attended their first or second birthday party,” said Lorinda Kiyama, a psychologist and associate professor at Tokyo Institute of Technology.

As an American living in Japan, Dr. Kiyama often counsels couples who come from different countries or international couples who are adopting a Japanese child. She pointed out that separation from relatives isn’t always a bad thing. “The distance is often a relief when relationships are fraught,” she said. However, “it can be agonizing when you want to be close.”

She suggested building familiarity by talking about absent relatives while pointing to photos of them. Babies as young as nine months may be able to recognize an object they’ve seen in a picture. And even if children seem too young to grasp what you’re saying, Dr. Kiyama said, they usually understand more language than they can produce.

With a parent’s help, a distant family member can use video chat to play peekaboo, sing songs with a child, do pretend play, or show off their pets. (And don’t worry if you’re trying to limit screen time: The American Academy of Pediatrics says video chatting doesn’t count.)

Ms. Mahbuba uses FaceTime to keep Aara in touch with her family in Bangladesh, though the time difference is a challenge. When Aara is alert and playful after her nap, it’s 2 a.m. for her grandparents.

Ms. Mahbuba said the enforced separation of the pandemic has given some of her friends and co-workers a window into what her life is like as an immigrant living far from her family. “They kind of understand now how it feels to be stuck,” she said.

Jumping the Gap

When long-absent family members finally get to meet those babies — or toddlers — it will be important to take their time building a relationship, said Carola Suárez-Orozco, a professor of counseling psychology at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, who has studied the effects of family separation on immigrant children. “Help the adults slow it down when they first encounter the baby.”

First, prime relatives for some amount of rejection from the child, Dr. Suárez-Orozco said. From a child’s point of view, “They’re meeting strangers.” Although younger infants might happily go from one set of arms to another, stranger anxiety develops by eight months or so. This fear of new people usually lasts well into the child’s second year.

“If a child is reluctant to hug an extended family member they just met, that should be seen as a healthy sign,” Dr. Kiyama said.

She suggested preparing toddlers for meeting relatives by using toys or stuffed animals to act out scenes like picking them up from the airport. You could also keep an empty chair at your kitchen table, or leave out a bath towel or other object, and tell the child it’s going to be Grandma’s when she visits, Dr. Kiyama said.

Older toddlers, or preschool-aged siblings who will be seeing relatives after a long absence, might like practicing what they’re going to say. “Give the child a script to follow, with some variations for flexibility,” Dr. Kiyama said. Or share memories of that relative from your own childhood.

For grown-ups who are connecting or reconnecting with a toddler or preschooler, parents are an important source of information, Dr. Schoppe-Sullivan said. Parents can help relatives get on a kid’s good side by updating them on the child’s temperament, interests and weird obsessions of the moment.

“From the emotional point of view of the adults, they have connected to an abstraction. They haven’t been bonding in those moment-to-moment interactions,” Dr. Suárez-Orozco said. In her study of immigrant children who had been apart from their parents for months or years — a much more extreme form of separation than what most families face during the pandemic — she saw that family reunifications were usually “messy.”

Even so, Dr. Suárez-Orozco and her co-authors wrote, the psychological distress these children felt after reuniting gradually ebbed, showing the “extraordinary adaptability and resilience of youth.”

Now that Ms. Mahbuba’s family in Bangladesh is in the process of getting their vaccines, she’s looking forward to her own reunion. Her mother-in-law is planning to come to the United States to help out with the baby, and Ms. Mahbuba can’t wait. “The day will come. Hopefully,” she said.

The gladness that parents feel to finally see their absent relatives will be one of the most important factors in helping a child warm up, Dr. Schoppe-Sullivan said. “Do things that are fun and that make them laugh. I think that makes a big impression on kids.”

Dr. Kiyama agreed. Young children are highly sensitive to how their caregivers feel about other people, she said. The best way to help kids accept a new family member? “Genuine joy in each other’s presence.”

We Want to See Your Pandemic Baby Family Reunions

Elizabeth Preston is a Boston-area science journalist and mom to a preschooler and a pandemic baby.

Advertisement